Acquired in 1842

Pair of Silver Reliquaries from the Dawson Collection

A small case of intrigue is opened when two unusual silver reliquaries are rediscovered.

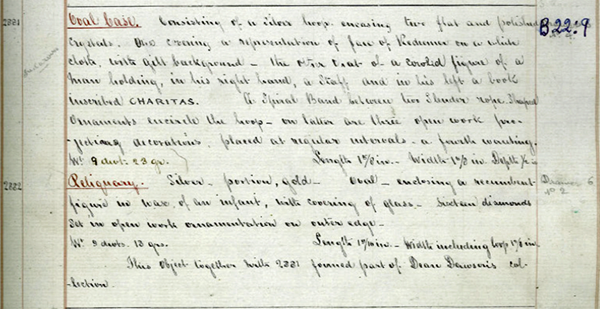

By Rachel FlynnA highlight of the Irish Antiquities Inventory Project must certainly be the opportunity to unearth beautiful and curious objects that have hidden modestly in drawers and boxes for many years, even decades. Two such objects are these silver reliquaries, originally part of the Dawson collection, which was acquired by the Royal Irish Academy in 1842.

A case of intrigue

The first, R2881, is a silver oval case with delicate filigree bosses, one on the bottom and one on each side. The top is damaged but, judging by the remaining fragments, did not have an equivalent boss and may have instead had a loop for suspension. The silver frame encases two miniatures which were probably painted directly onto the bevelled glass inlays. One side features a depiction of the face of Christ on a white cloth, possibly an interpretation of the Turin Shroud. The opposing side most likely depicts St Francis of Assisi in monastic habit.

Reliquary pendants in general have been popular since the medieval period with examples like this one mostly found from the 17th century onwards. Although manufactured in many countries, they are highly associated with Spanish colonial art, with many examples found in South America. Traditionally, a reliquary holds a fragment of a relic associated with a religious figure. It is quite possible that something precious has been sealed within this case, though we can only guess as to what it could be.

From birth to death

The second, R2882, is a gilt silver oval pendant with a decorative openwork frame into which sixteen diamante studs have been set. The centrepiece is a diorama featuring a wax figure of a recumbent baby surrounded by foliage, reminiscent of the infant Jesus in his manger.

This is quite a rare type, though a few similar examples appear from time to time and are generally considered to be representations of the Nativity. However, it is worth noting that it was once quite normal to have a wax effigy made of a deceased child, particularly in the Victorian era (1837- 1901). Infant mortality rates were much higher then and were an unfortunate fact of life for many parents. Practices that seem unusual to us now may have once afforded people the chance to individualise their bereavement in a time where over one in ten children died in infancy.

More than a feeling: emotions as objects

Both of these objects could be considered beautiful, or at least curious, in their own right. However, they were not created simply for ornament. Though we are missing a fragment from the top of our two-sided example, it is possible that both of these pieces were worn as pendants. From the beginning, personal adornment served more purposes than decoration. Reliquary pendants like these would have been worn as a demonstration of affiliation and worship; a medium between the wearer and their God.

From the Georgian era (1714- 1830) onward, we see the popularisation of the ‘memento mori’, which both commemorated the life of a deceased loved one and reminded the owner that this too would be their inevitable fate. Locks of hair and depictions of skeletons were common, but it was not unusual to find the use of other body parts, such as teeth, or the somewhat macabre posthumous portraits of those who had passed.

Dean Henry Richard Dawson

Henry Richard Dawson, the original owner of these objects was, in his other capacity, the Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral and Rector of Castlecomer. An active and highly regarded figure in the Liberties that surrounded his Dublin precinct, he devoted much of his energy to improving the circumstances of his parishioners, many of whom lived in abject poverty. His interest in antiquities seems to have predated his vocation and his collection can be dated back to his days as a student at Harrow.

At the time of his death, he had amassed a substantial and important collection of almost 2000 objects, largely of Irish origin. His original intention to bequeath his collection to the Royal Irish Academy was complicated when, following his untimely death from typhus at only 48 years old, it was discovered that he had not made a will. Fortunately, the Academy was able to purchase his collection by subscription and it became the foundation of the museum of the Royal Irish Academy, itself the foundation of The Museum today.

Learn more

This object is currently stored in the Irish Antiquities Reserve collection. You can see examples of medieval reliquaries in our Medieval Ireland 1150- 1550 exhibition, or visit our Decorative Arts and History museum to see examples of jewellery and dress from the Georgian era onwards in our exhibition, The Way We Wore. If you would like to see some reliquary pendants that were found in South America, the Brooklyn Museum has a small but interesting collection.

References

- Cave, E. (1841). Obituary- Very Rev. H. R. Dawson. The Gentleman’s Magazine. May, p. 536. London

- Mitchell, S. (1988). Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. New York, Garland Pub.

Suíomh:

Pair of Silver Reliquaries from the Dawson Collection suite ag:

In Storage

An déantán roimhe seo:

Pair of Egyptian Jars from a Ringfort at Lucan, Co. Dublin

An chéad déantán eile:

Pipefish from North Bull Island, Dublin