Traditionally the feast day of St. Patrick, observed on 17th March, St. Patrick’s Day is now a globally recognised celebration of Irish history, culture, and heritage.

Whether you are at home or in the Museum, you can explore the histories of these artefacts that showcase different symbols used to represent Ireland through time, in honour of St. Patrick's Day.

All artefacts are currently on display in the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks.

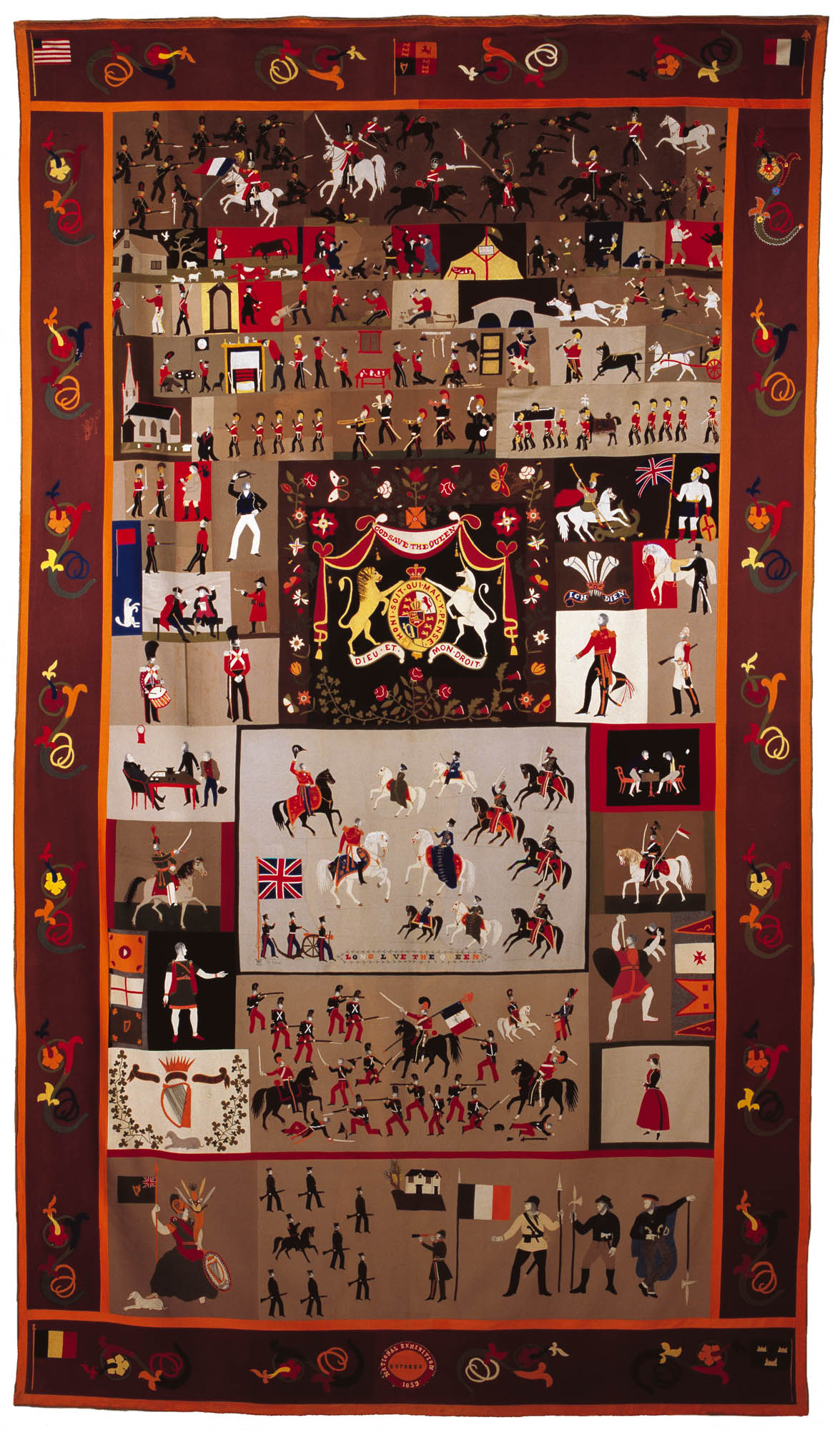

1. Stokes Tapestry, Soldiers and Chiefs, Gallery 15

Stephen Stokes (1802-1900) was a British Army soldier. He created this remarkable textile while he was stationed in Collins Barracks. Over 30 sewn panels tell the story of his career, first in the Royal Dragoons, a cavalry unit, and then in the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Stokes spent more than 15 years working on the intricately decorated tapestry. Notably, it is one of the first visual objects representing the Irish tricolour, seen in the bottom-most panel which illustrates the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848. Another Irish emblem appears in the form of Hibernia, a female personification of Ireland. Stokes depicts Hibernia as a warrior, wearing a helmet and bearing a shield emblazoned with the Irish harp. She also carries a battle standard with a version of Irish flag used at the time. Above the panel of Hibernia is the Irish harp around which a banner reads "Erin Go Bragh." In Irish this popular slogan is "Éireann go Brách," which translates to "Ireland for eternity."

.jpg)

2. St. Molaise Statue, Curator's Choice, Gallery 1

St. Molaise was a 6th century Irish bishop who founded a monastery on Inishmurray, a small island which lies about eight kilometres off the northwest coast of Sligo. This statue would originally have been placed on the island alongside many other images and buildings dedicated to the saint. This statue is a superb example of medieval craftsmanship, with its elegantly carved drapery and ascetically angular face. There was a belief that the back of the statue was hollowed out so that the Roman Catholic islanders could use it as a boat and escape to the mainland in times of religious persecution. Ireland's monasteries were hugely important cultural and intellectual centres in the medieval world, recording and producing knowledge for future generations. For this reason, Ireland is known as the Land of Saints and Scholars.

3. William Smith O’Brien Cup, Curator's Choice, Gallery 1

This commemorative object is decorated with symbols of both Ireland and Australia. The Irish nationalist politician William Smith O’Brien was transported to Tasmania due to his leadership during the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848. When he was pardoned six years later, he was honoured by his compatriots with this presentation cup, made from 24 carat gold. The cup was commissioned from William Hackett, a Dublin goldsmith then resident in Melbourne. The top depicts Hibernia carrying a cap of liberty and crowning Smith O’Brien with a laurel wreath. Conscious of the sacrifice of his compatriots and the rich symbolism of the cup, Smith O’Brien bequeathed it to the Royal Irish Academy to ensure its preservation for posterity.

4. Mether, Curator's Choice, Gallery 1

A ‘meadar’ or ‘mether’ is a wooden vessel originating from at least the 10th century that was designed with either two or four handles for communal drinking during feasts or ceremonies. Methers were also used for measuring: the name derives from the Latin ‘metrum’ meaning a measure. In Ireland, they commonly stored butter as well. In certain areas of the country, methers were used all the way into the 19th century. With the revival of interest in Irish history in the 19th century, the mether came to be recognised as a symbol of ancient Ireland and inspired artists, jewellers and metalworkers to make methers in a variety of media including precious metals and bog oak. For example, the design of the GAA's MacCarthy Cup, made from silver and awarded annually to the winners of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, is based on a mether.

To learn more about the history of methers, see here.

5. Presentation Casket to Charles Stewart Parnell, Out of Storage, Gallery 2

This box was presented by "the Nationalists of Drogheda" to the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell in 1884. It is part of the tradition of “Freedom Boxes,” given to people who were granted the honour of ‘Freedom of the City.’ The box, made by the silversmithing company Hopkins and Hopkins, has a roof-like lid with figures of a wolfhound, the famous ancient Irish dog breed, and of Hibernia. There are interlaced designs and Irish motifs such as shamrocks, monastic round towers, and wolfhounds at each corner of the casket. At the front of the casket, there is an image of the former Parliament building near Trinity College Dublin. Though it was the world's first purpose-build parliament building, it is today a Bank of Ireland building. In the late 19th century, the building was used by constitutional Nationalists as a symbol for Irish Home Rule. Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin is pictured on the left at the front of the casket, as Parnell negotiated the successful ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ on behalf of Irish tenant farmers whilst he was imprisoned there.

6. Triptych of St. Patrick's Life, Out of Storage, Gallery 2

This triptych, or artwork in three parts, depicts scenes from St Patrick's life. It was commissioned by the Museum to encourage enamel-working in Ireland. Made from brass inlaid with silver and painted with enamels, the triptych was painted around 1903 by Alexander Fisher. Although St. Patrick is Ireland’s most famous saint, he was not actually Irish-born! Living in the 5th century, St. Patrick is thought to have come from Wales and been brought to Ireland, where he did missionary work around the island. He is credited with converting the Irish to Christianity, using the three leaves of a shamrock to explain the nature of the Holy Trinity, shown in the lefthand panel. The central panel of the triptych shows a scene from his missionary work, when he converted the High King of Ireland King Laoghaire’s two daughters to Christianity.

7. Egan Harp, Out of Storage, Gallery 2

The harp has been used as a symbol of Ireland since the medieval period, when Ireland became part of Britain. It was officially adopted as a national symbol with the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. Interestingly, Ireland is the only country in the world to have a musical instrument as its national symbol. The design is based on the medieval Brian Boru harp, housed in Trinity College Dublin. This harp was made by John Egan, a harp maker based in Dawson Street in Dublin city between 1815 and 1835. He is most famous for his invention of the ‘Royal Portable Harp,' on display here. Though the design is based on the medieval Irish harp, the strings are much more flexible, allowing a greater range of sounds to be produced. Egan harps were typically decorated with hand-painted gold shamrocks on a dark background, which served to reinforce their Irish connection.

To hear an Egan harp being played, please click here.

8. Bell Shrine Replica, Irish Silver, Gallery 4

This is a 19th century replica of the Shrine of St Patrick's Bell. The original shrine, housed at the National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology, was made around 1100. Although it is unlikely that the bell itself was ever used by St. Patrick, he is credited with introducing ecclesiastical bells to Ireland. The firm of Edmond Johnson, who made this replica shrine, exhibited and sold many replicas of ancient Irish metalwork at the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893. This piece belongs to a larger trend of Neo-Celtic artwork that celebrated Ireland’s ancient past by mimicking Celtic art styles. This is demonstrated by the panels of interlace, the encased gems, and the stylised animal forms. More examples of Neo-Celtic objects are on display surrounding the bell shrine in our Irish Silver galleries.